Closing the gap

The biggest US banks have significantly higher outlays on information technology (IT) than their larger counterparts in Japan. What many may not realize, however, is that the truth about IT investments and strategies among Japanese banks is more complex than a simple comparison of total spending would suggest. For instance, while Japanese banks spend less on IT in absolute terms, their spending per employee is on par with that of large US banks. Furthermore, Japanese banks actually spend more than their US equivalents in a number of core banking areas, principally as a result of inefficiencies in the Japanese model. The main reasons Japanese investments in IT lag those of American banks in overall terms are the differences in customer and business needs and the emphasis on customer service and relationships by US banks. Looking ahead, the apparent “technology gap” between US and Japanese banks is likely to diminish significantly over the next few years, as financial institutions in Japan adapt to a rapidly changing environment.

Introduction

Conventional wisdom has it that a substantial "technology gap" exists between Japanese and US Banks. Past underinvestment in information technology means that it can take two weeks to obtain mortgage approvals. Internet banking services are in their infancy, ATM hours of availability are restricted and call center service is basic when compared to the US. Indeed, for much of the 1990s, many Japanese banks disinvested in IT, as financial woes plagued them and forced broad-based cost cutting. However, since the most recent Japanese financial crisis began in late 1997 with the collapse of the Hokkaido Takushoku Bank, the Japanese banking industry has begun restructuring and IT strategy has emerged as a hot topic for banks and their advisors. This new found emphasis on IT stems follows the competitive spur given by industry consolidation: many of Japan’s largest banks have disappeared, helping to create a more competitive environment in which the main participants are increasingly looking to IT to provide them with a competitive edge. As banks in Japan try to develop a strategy to help them be successful going forward, they are focusing attention on practices in other parts – particularly the US.

Lower spending

A long-standing question is the extent to which Japanese banks lag their American counterparts in deployment of information technology. Despite their enormity, the largest Japanese banks spend far less on information technology than their counterparts in any major global markets. The leading Japanese banks are 8 to 10 times larger than their US equivalents, in terms of assets per employee, but IT spending by the individual institution is a fraction of US levels.

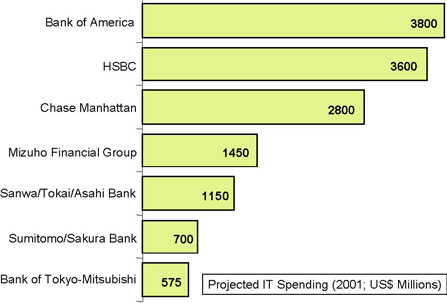

Chart 1 shows TowerGroup projections for IT spending by major Japanese banks in 2001. For comparative purposes, the exhibit also includes anticipated IT spending by major Western banks. Outlays on IT among US banks accomplish more than IT expenditures by Japanese banks for a number of reasons:

- The choice of external software available to Japanese banks is relatively limited;

- The complexity of the Japanese language and alphabet makes for greater processing and storage needs and limit the availability of software applications;

- Unit costs are higher in Japan as banks depend more on proprietary systems and in some cases incur avoidable costs by deploying expensive mainframe environments to process low volume transactions.

Part of the problem now facing banks results from their tardiness in adopting new technologies and providing services demanded by their customers. Most of the larger Japanese banks offer Internet banking services, but rollout has been slow relative to the US and some European markets. Only recently (October, 2000) did Japan’s first virtual bank, Japan Net Bank, come on-line. But changes are occurring. For instance, credit scoring is gradually being introduced for small business lending as banks seek efficiency gains in servicing the small business sector, while at the same time streamlining the credit application process for businesses.

Chart 1

Leading Japanese Banks Spend Far Less on IT Than Western Counterparts

Source: TowerGroup

Reflection of requirements

A number of factors help explain the differences between similarly-sized US and Japanese banks’ IT spending profiles:

Less “Back-Office” Work and High-Volume Applications Needed in Japan. US banks require more IT support for their business operations—much of it relating to back-office functions. In other words, more back-office work is needed per customer in the US market than in Japan. This is partly due to the fact that consumer behavioral patterns differ so that, for example, individuals in Japan use wire transfer and direct credit to pay most monthly bills. Importantly, financial EDI is likely to replace the small number of checks still in use, reducing the scope for Internet-related payment services to replace checks, as is the case in the US. Since Japan never had the huge check processing infrastructure built up in the US and elsewhere, it has been much faster to move toward electronic payments. In addition, although credit card companies have been established in Japan for the past 20+ years, it was not until 1992 that the Ministry of Finance permitted revolving credit. (Before that, all balances had to paid in full at the end of the month.) In fact, no unsecured lines of credit of any kind had been allowed. With the advanced, highly automated payment mechanisms already in place, and the predisposition for consumers to pay cash for many day-to-day transactions, the scope for credit and debit card penetration is limited, as demonstrated by the low and declining number of merchant terminals handling electronic payments at the point-of-sale. US banks, by contrast, need a more substantial technology infrastructure to support check and card processing and statement generation.

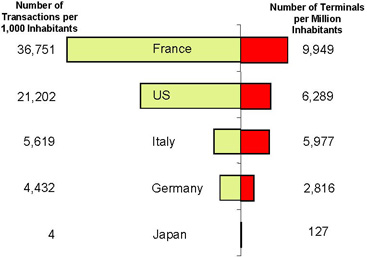

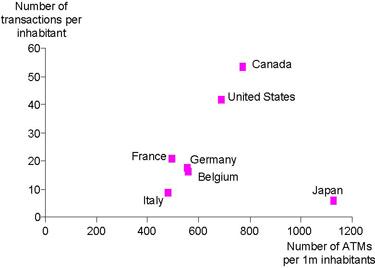

Day-to-day Purchases are often by Cash in Japan, Rarely by Card. Debit cards are virtually nonexistent in Japan (see Chart 2). Japan’s relatively high population density and low crime rates support the importance of ATMs and dependence on cash as a means of payment. Japanese consumers use ATMs less frequently (due, in part, to lack of availability of 24×7 access) than do consumers in other major markets (Chart 3). US banks, by contrast, need a more substantial technology infrastructure to support check and card processing and statement generation.

Differing Corporate Business Needs and Requirements. With very low prevailing real and nominal interest rates, Japanese banks place little emphasis on cash management services that are so important in the US marketplace. The relative absence of services such as cash management eliminates the need for substantial IT infrastructures seen in the US and other Western markets.

“Closed” IT Infrastructure. Japan’s banks have traditionally turned to Japanese hardware and software vendors to fulfill their IT needs. Many Japanese banks do not use operating environments that are common elsewhere, such as CICS and MVS, as do US banks, thus limiting the range of software vendors from which they may choose. Dai-Ichi Kangyo (DKB), for instance, uses accounting systems developed by Fujitsu, while IBJ uses Hitachi-supplied hardware. Likely results of this dependency on indigenous IT are inefficiencies that give rise to higher unit costs and reduced ability to integrate newer software applications, with enhanced functionality, developed for hardware environments that are more common in the US and Europe. For example, costs per banking transaction, such as an ATM withdrawal, are far higher in Japan, partly because Japanese banks depend on proprietary systems and use costly mainframes to handle transaction volumes that could be handled by less costly hardware alternatives. Chart 3 illustrates TowerGroup estimates of IT spending at Dai-Ichi Kangyo. IT spending on existing systems absorbed about 60% of total IT spending during 1999. At other Japanese banks, systems for day-to-day operations, as opposed to new development, account for as much as 70–80% of total IT spending. However, the dependency on Japanese suppliers is waning. Sumitomo Bank, for instance, began offering telephone banking in 1997, using hardware supplied by IBM Japan.

Japanese IT Investments More Narrowly Targeted. Japanese banks have invested relatively little in areas that are focus points of US bank IT investment, such as remote services, risk management, capital markets, payment processing, corporate trust, etc. Instead, core banking systems have continued to account for a significant proportion of total IT budgets at Japanese banks.

Delivery Channels More Limited in Japan. Call centers are relatively rare in Japan and it is widely accepted that Japan significantly lags the US in deployment of modern technologies in this area. Internet banking is beginning to become popular—but, again, is relatively limited compared to the situation among major US institutions.

Aversion to Outsourcing. Traditionally, Japanese banks have developed home-grown IT systems and not shown much interest in outsourcing IT functions - notwithstanding the arrangement by which a number of small credit institutions outsource their core systems to data centers run by their bankers’ associations. Cultural issues underlie this trend: (1) “life-time employment” for employees does not fit well with the concept of using outside vendors in place of in-house expertise and (2) Japanese banks have traditionally been managed by people with little or no strategic IT focus. This is starting to change, partly due to the fact that US and European vendors are sometimes ahead of their Japanese counterparts in their product offerings, with the result that Japanese banks may have little or no choice but to use non-Japanese vendors if they wish to offer service through a new delivery channel, offer a new product, etc. Some banks are arranging alliances with vendors, such as Daiwa Bank’s joint venture with IBM Japan, who are creating a separate, jointly held company to handle Daiwa’s IT hardware needs under a 10-year contract arrangement. But it is not just hardware vendors that are benefiting: software vendors such as Germany’s Brokat Systeme are providing software to banks interested in offering Internet and wireless banking services.

Chart 2

Electronic Funds Transfers at Point of Sale: Little Supporting Infrastructure in Japan

Note: Data shown are for 1998.

Sources: TowerGroup and Bank for International Settlements

Chart 3

More ATMs Mean More Usage – Except in Japan

Note: Data shown are for 1998.

Source: TowerGroup and Bank for International Settlements

An IT Spending revival

Japanese banks’ IT spending declined during the period 1989–95 as financial problems plaguing the major banks gave rise to cutbacks in many areas, including information technology. Since then, there has been an upward trend in IT spending at many Japanese banks owing to several factors.

One such factor is mergers. Mergers are encouraging banks to rethink their technology infrastructures and future needs. Fuji Bank, for instance, has publicly committed itself to substantially investing in IT over the next few years, using resources freed through its proposed merger with two other large banks.

Another factor encouraging greater IT spending by Japanese banks is increasing competition from nontraditional sources. Increasingly, US and European institutions are leveraging their global brands by developing a presence in the Japanese market, as former barriers break down. Consequently, Japanese banks are being encouraged to accelerate efforts to improve value for their customers by offering new products and services, accepting higher risk endeavors as a means of improving profits and holding on to marketshare. To do so, banks are investing in IT solutions that assist in the monitoring and management of risk and in aggregating the positions (and potential liability) of the bank. As part of this, integrating market and credit risk management by automating data transfer between front, middle, and back offices by straight-through-processing (STP) is a high priority for larger institutions. Spurring this investment has been the serious losses Japanese banks incurred as a result of bad loan write-offs.

Finally, banks are facing a regulatory change that will require them to add more customer value or face decline. Most likely within the next year or so, 100% deposit insurance for bank customer deposits will end. Banks realize that a likely scenario is for a decline in deposits and a need for banks to develop new sources of funds. Very soon, they will need to be able to identify and keep profitable customers and provide services to them in the way and at the time that the customer wants it. If they are to prosper, CRM will start becoming really important to Japanese banks, and with it, investments in the core components of CRM, namely datawarehousing, datamining, marketing and service components.

The Outlook for 2001 and beyond

Relative to their size, Japanese bank revenues are much lower than those of major Western banks, in part as Japanese banks are predominantly wholesale banks: lending to corporations who are unable, due to the immaturity of capital markets, to borrow by issuing debt on the bond markets. As capital markets’ deregulation unfolds, and the Financial Supervisory Agency winds down, banks will be encouraged to turn more to the retail sector to grow revenues and restore profitability. To be successful in an environment in which they will have serious competition in attracting, retaining and expanding their relationships with retail customers, they will need to invest in newer technologies to improve customer service, identify profitable customers and manage the sales process.

From a vendor standpoint, opportunities will present themselves in a number of areas. Sales automation tools will be needed as banks start to look for cost savings in customer acquisition and begin to focus more on cross-selling. With Japanese banks’ relative lack of customer-based systems, marketing customer information, performance reporting and other information systems suggest an opportunity as banks reinvent themselves in the coming period.

Overall, Japan’s banks have traditionally viewed information technology as forming part of a support function – not as a differentiating or competitive factor in its own right. This will inevitably change as competition from overseas, coupled with domestic pressures to restore profitability, force banks to rethink their IT strategies and cease viewing cutting edge technology as unnecessary, unstable and risky.

Michael J. McEvoy is a co-founder of Nechtain LLC

www.nechtain.com