Mergers and Acquisitions: Viewing the Whole Picture

Bank mergers are a common feature of the business landscape in the developed world and have been for some time. Motivations for merger vary by individual case, but frequently cited is the desire to search for cost savings. In an increasing number of merger announcements, the information technology (IT) function is singled out as an area of significant anticipated savings. The increased importance given to the IT issue stems, in part, from the growing share of technology outlays in the operating expenses for large institutions in developed markets. However, while mergers do offer the potential for IT cost savings, realizing those gains is more complex.

Sources of Efficiencies through Merger

When banks merge, typically, savings are expected to accrue from three main sources: branch closures, staff reduction and consolidation of technology infrastructures.

Branch closings and staff reduction may be relatively straight-forward, in terms of where they should occur and how feasible they are with respect to the bank's outside image and its internal staff relations. Regulatory agencies may also play a role in decisions on branches.

Technology issues are more difficult. Before discussing these issues, it is worth considering how mergers can be a source of efficiencies and cost savings in the supporting information technology infrastructure:

Data Centers. Data centers are intensive users of IT resources and a significant area of spending for virtually all large banks. Here, we see the greatest potential for saving but the greatest likelihood for disappointment (less than 50% of the potential savings will likely materialize), given the complexity of data center integration and the political difficulties associated with abandoning substantial pre-existing investments. As much as 40% of the savings in IT costs that are possible through bank mergers relate to expenditures connected with data centers.

Best of Breed. Banks sometimes take the opportunity afforded by a merger to reconsider the IT applications used to handle certain parts of their business. Applications in use at the time of merger may be incapable of handling the higher volumes at the new entity, or they may be based on older technology. The result can be a “best-of-breed” approach in which the new bank entity might select a replacement IT system to handle, say, car loan applications.

Buyer Pressure on Suppliers. As in any industry, the larger entities that result from the mergers can be expected to obtain more favorable pricing terms. Moreover, software vendors, particularly those that are smaller and more specialized, sometimes find it advantageous to reduce prices for “big name” clients in order to sign them as clients, thereby gaining credibility with other sales prospects.

Electronic Channel Savings. Investments in electronic channels are often easier to integrate after a merger, given that many other forms of IT investments are based on older technologies or have a much higher proprietary component or both.

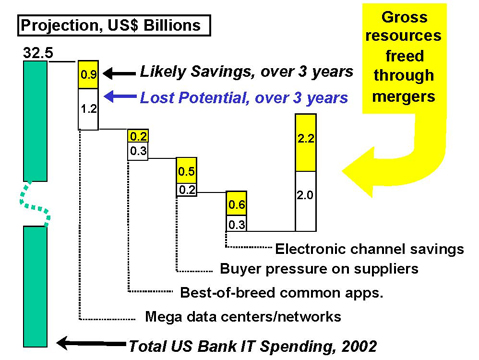

To illustrate these points, we might think of a waterfall situation, shown as Figure 1. At the time the merger is announced and approved, let’s say the combined bank’s overall IT spending amounts to $1 billion annually. Following approval for the merger from investors and regulators, it will take some time for full integration to occur, possibly several years. In our illustrative example integration occurs over three years. During this time, reorganization results in cost savings through data center consolidation, implementation of "best of breed" applications, and so on. The cost savings "free up" $110 million, after conversion costs, to be spent elsewhere, possibly on new technology applications.

Figure 1

Merger Activity Among Banks Is Creating Opportunities for Efficiencies in IT Investment

Source: TowerGroup

Complexity in Core Systems Selection

An area that is particularly challenging for merging institutions is that of core systems selection. All sectors of the financial services industry—banking, securities, investments, and insurance—rely on a group of core processing and product-specific applications that support product delivery. Clearly, as the range of products grows and institutions expand into new areas, possibly through merger, the core technology needs will also expand.

By using a single central database to support their various services and functions, banks can reduce the number of independent systems needed and potentially defer maintenance costs. The availability of this technology has also increased the complexity of the systems selection process, however, by creating a trade-off between modern technology infrastructures and the features of the more mature systems. Indeed, selecting a core banking system is a very difficult proposition. There are many diverse functions to support, and core systems must also be considered in the context of a fully functional systems scenario to make a fair comparison.

The systems selection process for core systems at a large bank which operates in diversified businesses – often referred to as a "universal bank" – can either be based on systems replacement or form part of an organized program of organizational change. There is a significant difference between the two approaches. The system replacement approach scores a short list of systems on their features, functions, and vendor company attributes. The system with the highest score is enhanced to meet critical needs, if necessary, and then implemented.

An organizational change program, however, involves changes to the organization’s people, processes, and technology, undertaken in a co-ordinated fashion. The initiation of such a program requires management consensus and an accompanying business plan.

The two methods offer fundamental differences in their approach to prospective systems evaluations. The replacement approach is structured around functions and data fields. The change program is structured around process (e.g., roles, responsibilities, rules) and workflow. The latter method defines a theoretical business process, or target process, and then evaluates existing systems against it.

The types of functionality found in the system scenarios can be classified into seven categories: deposits, loans, asset custody, investment management, trading, dealing, and underwriting. While the systems they supply can each support many bank functions, it is unlikely that one system will match the target processes of every department at a given bank. As a result, a “typical” large bank will have between 5 and 15 systems comprising its architecture. Clearly, the importance of core application systems to any bank indicates the significance of the selection of those systems for merging entities.

Difficulties in Realizing Cost and Efficiency Gains

The problem with all this is that the potential cost savings through mergers are hard to achieve and probably never materialize in full. For one thing, there are different kinds of mergers, and the specifics of a merger broadly determines what is possible in terms of consolidation of the technology function.

Integration is simplest with "home market" mergers. With a “home market” merger, the merging entities operate in much the same market(s). For instance, the merger might be between two banks offering similar products and services, operating in the same geographic area. In such a situation, the prospects for being able to integrate the IT investments of the two entities and realize cost savings are better than in the case of an “out of market” merger in which the merging entities operate in mostly different markets.

Synergies are also harder to find when the participants to a merger operate in broadly different businesses. An institution that is focused on providing banking services to consumers is going to have to look hard to find ways of replacing or consolidating many of its systems with those of a commercial bank focused on corporate needs. The problem is that there are so many specialized software applications in use, handling specific products or services offered by the institution. Just as challenging are mergers between banks and non-banks, such as brokerage firms.

Even among "home market" mergers, the technology challenges can be very significant. Do the merging institutions utilize similar hardware and operating systems for their major applications? How scalable are the software applications currently in use and can existing systems cope with the transaction volumes of the merged entity? What are the relative strengths in terms of newer, emerging technologies, such as wireless and Web-based services? Do the two sets of customer-bases have different expectations in terms of how they communicate with their merging bank (e.g. Internet transaction capability, call center presence)? What about the relative internal political strengths of the merging bank's technology departments?

Above all, there is the challenge to consummate the merger as quickly as possible. The result is that, often times, there is little or no time for a grand re-evaluation of the merging institution's technology needs. Instead, the need for haste and cost considerations foster an approach that encourages quick solutions, not necessarily the best ones. What sometimes happens is a re-evaluation of supporting technology for certain select areas of the business, but not across all business lines.

With some kinds of mergers, the reality is that integration never occurs and little IT cost savings are realized. If the two merging banks operate in entirely different geographies (e.g. one bank operates mainly in Northern Europe, while the other bank is based in Latin America), for instance, the norm is for both to retain entirely separate systems – although, over time, there may be an effort to use software applications from the same supplier or vendor. Nonetheless, data sharing on customers and the creation of integrated customer files spanning the institution's customer base are not so common when the merging banks operate in different jurisdictions.

The Example of Chase Manhattan Bank

It is hard to argue that Chase Manhattan is a "typical" bank, given its enormous size and breadth of its business involvements. However, its experiences resulting from its merger with Chemical Bank are instructive for any merging banks and well worth exploring.

With over $400 billion in assets and nearly 75,000 full-time-equivalent employees worldwide in 1999, the Chase Manhattan Corporation is the third largest bank holding company in the United States and among the top 30 in the world. With a tradition of growing through large mergers, Chase Manhattan now boasts a huge customer base as well as a worldwide presence in the financial industry. Today, the bank’s services range from investment banking and global markets operations to private banking, credit cards, home finance, and consumer banking services.

Chase and Chemical announced their intentions to merge on August 28, 1995. Significantly, in the context of the earlier discussion, the integration of the information technology infrastructures of the two banks was conducted at great speed. Within a few months of the announcement of the merger, for example, most of the systems recommendations had been completed, and by February 1996, all new systems selections were completed. Consolidating all systems of a bank this size was a huge challenge, but recent experience with the merger of Chemical Bank and Manufacturers Hanover Trust helped the management team progress quickly. Two key methodologies, the Merger Overview Model and the Technology Integration Model, that had been developed during the previous merger helped provide detailed project information and status reports. Furthermore, A.T. Kearney contributed high-level risk management methodologies to prioritize projects and tasks.

Among the many integration efforts, the consumer banking system conversion was timely for Chase. Even before the merger, Chase had been considering an overhaul of its consumer banking system, while Chemical had recently installed a comprehensive system partly based on a software suite from ALLTEL. The obvious decision was to leverage Chemical’s system. Consolidation of the consumer banking systems involved creation of a consumer information file with over 9.7 million customers and 16 million accounts.

Meanwhile, Chemical had been looking for a new global custody platform for securities processing and other investor services. Fortunately, Chase was a leader in global custody and was running a world class system. Again, a lengthy systems evaluation and selection was avoided.

The general ledger was yet another critical systems conversion. Chase was using decentralized general ledgers and sub-ledgers and was hoping to move toward a centralized architecture before the merger. Chemical was using a single, centralized ledger, Dun & Bradstreet’s MSA. Slowly, over a period of 20 months, the joint bank moved over to MSA and phased out Chase’s old general ledger system.

While the integration costs were significant, the merger was to result in $1.7 billion in annual cost reductions for the new Chase. This would be accomplished in part by reductions in staff, including IT staff. The technology contribution to the annual merger savings came from systems conversions. The new consumer banking system, for example, saved an estimated $250 million annually.

In the Chase/Chemical merger, we see a great example of a pair of banks that sought quick integration and had little appetite for a lengthy, formal re-evaluation of existing technologies. Some of the potential cost savings were likely lost in the process, but the merger itself was successfully completed.

Figure 2 summarizes some of the major milestones as part of the Chase/Chemical merger.

Figure 2

Chase/Chemical Merger: Technology Milestones

|

Date |

Event |

|

1995 |

|

|

August |

Chase and Chemical announce intention to merge. |

|

December |

Most systems recommendations completed |

|

1996 |

|

|

February |

Systems selections completed |

|

March |

Holding companies merged; financial systems bridged; global trading operations combined

|

|

July |

Single general ledger and funds transfer system completed |

|

August |

Customer information file for consumer banking system created |

|

October |

Identities unified under Chase logo; consumer banking operations merged |

|

1997 |

|

|

April |

Consumer banking system conversion completed |

|

1998 |

|

|

December |

All systems consolidations and conversions complete |

Source: TowerGroup

Outsourcing As a Solution?

A possible solution to some of the challenges of realizing cost savings through merger is to outsource some or all of the technology function. Indeed, one of the most important trends in US financial services for a number of years has been disaggregation of the IT function and the practice has begun to emerge in other geographies such as Northern Europe and parts of Asia. Financial institutions are outsourcing many disparate functional capabilities required to create, deliver, and service their products and services. Specialist companies, such as credit bureaux and collection agencies, produce parts of the product that are combined to form the overall product.

Outsourcing has gained popularity as institutions seek ways of remaining focused on their core businesses while at the same time tapping into a cost-effective means to remaining competitive in terms of technology. Many examples exist of the types of areas in which outsourcing has become widely accepted:

- Banks outsource more than 20 per cent of check processing.

- Securities firms routinely outsource the clearing and settlement function.

- Institutions, particularly in banking, are choosing more packaged solutions than developing proprietary solutions in-house.

- In consumer credit, major service bureaux have emerged for credit card and mortgage that provide specialized, niche services such as credit evaluation and collection services.

- It is not uncommon in any segment of US financial services for data center, application maintenance, local area network (LAN) maintenance, and new systems development to be outsourced.

As industry convergence gains momentum, the trend toward outsourcing and use of third-party solutions will likely accelerate and become more commonplace worldwide. Merging parties, in particular, will increasingly begin to see outsourcing as an alternative, as the opportunities to outsource become more readily available.

Conclusion

One of the characteristics of the IT infrastructure at most banks is that it consists of a mix of disparate systems and technologies that are difficult to integrate as part of a merger. At the same time, mergers may afford the opportunity for the bank to “stand back” and reorganize its technology function to better prepare it for the future and realize cost savings while it is getting there. The problem is taking the time and devoting the resources to accomplish this, but for those who do, the benefits can be immeasurable.

Michael J. McEvoy is a co-founder of Nechtain LLC

www.nechtain.com