Is there a “technology gap” between US and Japanese banks and will it persist?

Laggards at IT?

Conventional wisdom has it that Japanese banks are laggards when it comes to information technology (IT). Indeed, for much of the 1990s, many Japanese banks disinvested in IT, as financial woes plagued them and forced broad-based cost cutting. However, since the most recent Japanese financial crisis began in late 1997 with the collapse of the Hokkaido Takushoku Bank, the Japanese banking industry has begun restructuring and IT strategy has emerged as a hot topic for banks and their advisors. This new found emphasis on IT stems follows the competitive spur given by industry consolidation: five of Japan’s 20 large banks have disappeared, helping to create a more competitive environment in which the main participants are increasingly looking to IT to provide them with a competitive edge. As banks in Japan try to develop a strategy to help them be successful going forward, they are focusing attention on practices in other parts – particularly the US.

IT spending comparisons are difficult

A long-standing question is the extent to which Japanese banks lag their American counterparts in deployment of information technology. Despite their enormity, the largest Japanese banks spend far less on information technology than their counterparts in any major global markets. The leading Japanese banks are 8 to 10 times larger than their US equivalents, in terms of assets per employee, but IT spending by the individual institution is a fraction of US levels.

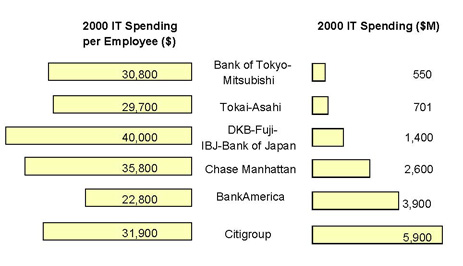

Chart 1 shows total IT spending by selected institutions in both the US and Japan. US banks clearly spend a lot more, in absolute terms (right-side in chart 1) than their larger counterparts in Japan. Nonetheless, this inference can be misleading. As the left hand side of Chart 1 shows, while Japanese banks spend less on IT in absolute terms, spending per employee is on a par with that of large US banks.

Chart 1

Japanese Banks Spend Less on IT Than US Banks, but Spending per Employee Is on a Par

Note: Data shown are projections.

Source: TowerGroup

Even more interesting is to look at IT spending profiles of Japanese and US banks. As discussed below, Japanese banks actually spend more than US banks in certain core areas – in part, an outcome of inefficiencies in the Japanese model. At the same time, US banks invest substantially more than Japanese counterparts in areas that receive little attention in Japan, such as electronic funds transfer. This helps explain the observed disparity in total spending between larger institution in both markets and the apparently contradictory evidence that Japanese banks face higher IT unit costs with their IT investments.

Differences in IT spending profiles between US and Japanese banks reflect different business requirements

Although IT spending per head is comparable between US and Japanese banks, IT dollars spent by US banks accomplish more, on average, than those spent in the Japanese financial sector, for reasons detailed below. More generally, a number of factors help explain the differences between similarly-sized US and Japanese banks’ IT spending profiles:

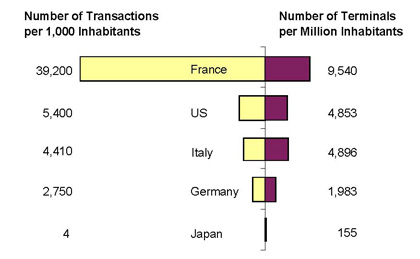

Less “Back-Office” Work and High-Volume Applications Needed in Japan. US banks require more IT support for their business operations—much of it relating to back-office functions. In other words, more back-office work is needed per customer in the US market than in Japan. This is partly due to the fact that consumer behavioral patterns differ so that, for example, Japanese consumers are more likely to use cash payments rather than check or credit card. Debit cards are virtually nonexistent in Japan (see Chart 2). Japan’s relatively high population density and low crime rates support the importance of ATMs and dependence on cash as a means of payment. Japanese consumers use ATMs less frequently (due, in part, to lack of availability of 24×7 access) than do consumers in other major markets. US banks, by contrast, need a more substantial technology infrastructure to support check and card processing and statement generation.

Differing Corporate Business Needs and Requirements. With very low prevailing real and nominal interest rates, Japanese banks place little emphasis on cash management services that are so important in the US marketplace. The relative absence of services such as cash management eliminates the need for substantial IT infrastructures seen in the US and other Western markets.

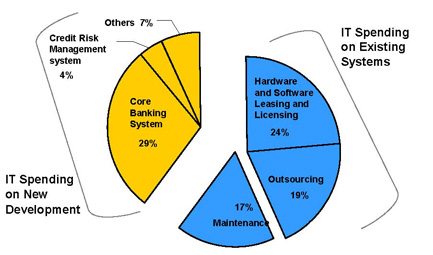

“Closed” IT Infrastructure. Japan’s banks have traditionally turned to Japanese hardware and software vendors to fulfill their IT needs. Many Japanese banks do not use operating environments that are common elsewhere, such as CICS and MVS, as do US banks, thus limiting the range of software vendors from which they may choose. Dai-Ichi Kangyo (DKB), for instance, uses accounting systems developed by Fujitsu, while IBJ uses Hitachi-supplied hardware. Likely results of this dependency on indigenous IT are inefficiencies that give rise to higher unit costs and reduced ability to integrate newer software applications, with enhanced functionality, developed for hardware environments that are more common in the US and Europe. For example, costs per banking transaction, such as an ATM withdrawal, are far higher in Japan, partly because Japanese banks depend on proprietary systems and use costly mainframes to handle transaction volumes that could be handled by less costly hardware alternatives. Chart 3 illustrates TowerGroup estimates of IT spending at Dai-Ichi Kangyo. IT spending on existing systems absorbed about 60% of total IT spending during 1999. At other Japanese banks, systems for day-to-day operations, as opposed to new development, account for as much as 70–80% of total IT spending. However, the dependency on Japanese suppliers is waning. Sumitomo Bank, for instance, began offering telephone banking in 1997, using hardware supplied by IBM Japan.

Japanese IT Investments More Narrowly Targeted. Japanese banks have invested relatively little in areas that are focus points of US bank IT investment, such as remote services, risk management, capital markets, payment processing, corporate trust, etc. Instead, core banking systems have continued to account for a significant proportion of total IT budgets at Japanese banks. It is worth noting that the bulk of DKB’s IT spending, even on “new” systems, relates to core banking areas – not Internet delivery, CRM and other “hot” areas emphasized by US banks.

Delivery Channels More Limited in Japan. Call centers are relatively rare in Japan and it is widely accepted that Japan significantly lags the US in deployment of modern technologies in this area. Internet banking is beginning to become popular—but, again, is relatively limited compared to the situation among major US institutions.

Aversion to Outsourcing. Traditionally, Japanese banks have developed home-grown IT systems and not shown much interest in outsourcing IT functions. Cultural issues underlie this trend: (1) “life-time employment” for employees does not fit well with the concept of using outside vendors in place of in-house expertise and (2) Japanese banks have traditionally been managed by people with little or no strategic IT focus. This is starting to change, partly due to the fact that US and European vendors are sometimes ahead of their Japanese counterparts in their product offerings, with the result that Japanese banks may have little or no choice but to use non-Japanese vendors if they wish to offer service through a new delivery channel, offer a new product, etc. Some banks are arranging alliances with vendors, such as Daiwa Bank’s joint venture with IBM Japan, who are creating a separate, jointly held company to handle Daiwa’s IT hardware needs under a 10-year contract arrangement. But it is not just hardware vendors that are benefiting: software vendors such as Germany’s Brokat Systeme are providing software to banks interested in offering Internet and wireless banking services.

Chart 2

Electronic Funds Transfers at Point of Sale: Little Supporting Infrastructure in Japan

Note: Data shown are for 1997.

Sources: TowerGroup and Bank for International Settlements

Chart 3

IT Spending Breakdown at DKB, 1999

Note: “Core Banking System” in this exhibit refers to loan systems, deposit systems, teller support systems, and ATMs.

Source: TowerGroup

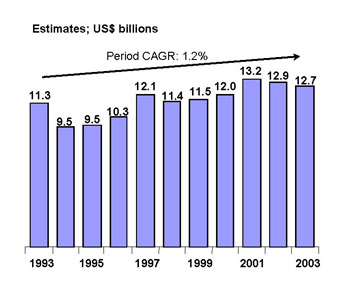

IT spending among Japanese banks: A revival in store

TowerGroup estimates Japanese banks’ total outlays on IT to have been $11.5 billion during 1999, an increase of almost 1% from the 1998 level (see Chart 4). Japanese banks’ IT spending had declined during the period 1989–95 as financial problems plaguing the major banks gave rise to cutbacks in many areas, including information technology. More recently, there has been an upward trend in IT spending at many Japanese banks, such as DKB, owing to several factors.

One such factor is mergers.

Although analysis of past expenditures suggests that IT investments by banks in Japan have been narrowly focused in a small number of areas, recent merger activity is spurring a different kind of behavior by banks. The largest proposed merger, for instance, that between Dai-Ichi Kangyo Bank (DKB), Bank of Japan, and Fuji Bank, involves a plan to invest in IT to increase the number of automated branch outlets as part of a broader plan to restructure its customer offerings. The new group expects IT spending to approximate $1.4 billion (150 billion yen) annually – rivaling all but the very largest US banks.

Japan has 18 banks that are the equivalent of US money-center banks—a number that will inevitably decline as more mergers occur. With mergers of such banks come opportunities to reinvest in new technology resources that are freed through the integration of operations. Fuji Bank has publicly committed itself to substantially investing in IT over the next few years, using resources freed through its proposed merger with two other large banks.

Banks currently undergoing mergers have emphasized IT investments as playing an important role, both in bringing about a successful merger and as a critical vehicle to enable them to compete with US institutions in the home market. Mergers are driving banks to rethink IT strategies and focus on improving efficiencies through the adoption of modern IT infrastructures.

Another factor encouraging greater IT spending by Japanese banks is increasing competition from nontraditional sources. Increasingly, US and European institutions are leveraging their global brands by developing a presence in the Japanese market, as former barriers break down. Consequently, Japanese banks are being encouraged to accelerate efforts to improve value for their customers by offering new products and services, such as Internet banking.

Additionally, the serious losses Japanese banks incur as a result of bad loan write-offs have encouraged efforts to rely more on information technology to manage risk exposure and identify potential difficulties earlier.

Finally, banks are facing a regulatory change that will require them to add more customer value or face decline. In April 2001, 100% deposit insurance for bank customer deposits will end. Banks realize that a likely scenario is for a decline in deposits and a need for banks to develop new sources of funds. As banks add products and services to provide a more “complete” range of offerings for their respective customer bases, the demands on supporting information technology will give rise to accelerated spending.

Chart 4

Japanese Bank IT Spending Is Accelerating After Several Years of Stagnation

Note: Past and projected future IT spending data are adjusted for exchange-rate changes.

Source: TowerGroup

Japan, a hotbed of change

Japanese banks have traditionally spent substantially less on IT, overall, than similarly sized US institutions. This is starting to change, as Japanese banks face increasing competition from nontraditional sources and as financial sector reforms grip the industry. However, it is the merging banks that face the biggest challenges. Measured by returns on equity, Japanese money center banks are less profitable than similar banks in other major markets, principally the US and Western Europe. Looking ahead, Japanese banks will need to improve their success at cross-selling existing customers, managing costs, and leveraging IT investments post-merger. The future of a financial institution is likely to depend on the quantity and quality of its IT investments. Nowhere is this more true than Japan, currently a hotbed of change in the banking industry.

Michael J. McEvoy is a co-founder of Nechtain LLC

www.nechtain.com